“Oh, you’re an English major? That’s interesting.” An assuring nod, a brief pause. “So, what are you planning to do with that?

I’m often inclined to wince whenever I hear this question posited before me, especially when I’m introducing myself to someone new, because I sense in the words of my fellow questioner a subtle disregard. We share an intimation that my particular major isn’t quite as practical as, say, a degree in business. I love writing because I am able to express my deepest feelings and reflections in a way I’m not able to with any other artistic medium.

At the same time, I am uncomfortably aware of the fact that writing novels and poetry these days isn’t going to put bread on the table as easily as if I were practicing in a lucrative law firm. But the humanities are not the haven of idle philosophizing they are misperceived as; rather, they provide more practical life skills than we think.

Understandably, there has been a notable shift in students’ self-interests concerning the value of their college education. A recent New York Times article claims the purpose of college has been gradually transforming from receiving an all-encompassing education into establishing a credential-training ground that will guarantee graduates a decent job.

As a result, students are led to believe that degrees awarded within the humanities have decreased. According to a 2003 survey by the Humanities Resource Center Online of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, degrees went from 17.7 percent of all bachelor’s degrees awarded in 1970 to 6.7 percent in 2003. The absolute number of degrees awarded in the humanities declined, from 99,280 to 65,423 — during a period when total undergraduate enrollments at American colleges, according to the National Center for Education Statistics, increased by over 80 percent.

But despite many reports detailing the drop of humanities majors since the 1970s, the number of bachelor’s degrees in the humanities has grown steadily since its low point in the 1980s, with more than 185,000 degrees reported in each year from 2009 to 2011. In response, Pauline Yu, president of the American Council of Learned Societies, lamented this gradual departure from the former worth of a college education: “College is increasingly being defined narrowly as job preparation, not as something designed to educate the whole person.”

It is no surprise then that enrollment into a STEM (sciences, technology, engineering and mathematics) or business major seems more appealing among the college student populace than enrolling into the humanities. Due to the current high costs of attending college, the huge debt incurred through loans and the dominance of science and technology in the global marketplace, most students are inclined to pursue their undergraduate studies within the realms of the STEM and business administration departments, where the likelihood of finding a stable job with a good salary and paying off college debts is much more auspicious, rather than in an obscure but interesting major in the humanities.

However, the value of the humanities cannot be disregarded. The humanities are not just a realm of high-minded contemplation of philosophical questions with no practical value; they offer skills alongside technical facility essential to the workplace.

The most important skill the humanities teaches students is being prepared for an unpredictable variety of occupations. Having the industry-specific knowledge of a technical discipline is vital, but in the chance of being laid off because of economic setbacks, having the interdisciplinary skills to adapt quickly in another field of work is advantageous. A background in critical analysis helps individuals consider every possible interpretation of a problem and allows them to make prudent, well-informed decisions as to how to proceed.

Writing essays and research papers gets dull at times, but it improves our ability to articulate and communicate our ideas concisely and effectively on paper as well as in speech. To reinforce this sentiment, the Association of American Colleges and Universities recently published an article providing a detailed analysis of employers’ priorities for the kinds of learning college students need to succeed in today’s economy. According to the results of the survey, “three out of four employers want new hires with precisely the sorts of skills that the humanities teach: critical thinking, complex problem-solving, as well as written and oral communication.” In light of this information, we need to get out of the outmoded binary perception of the humanities and STEM as entities on opposing sides of the educational spectrum.

You may be familiar with conversations in which STEM students disparage humanities students for having it “easier” with essays and readings, whereas humanities students tremble to consider the calculus equations and labs STEM students deal with daily. It has become the common misconception that the humanities and sciences are at odds with each other.

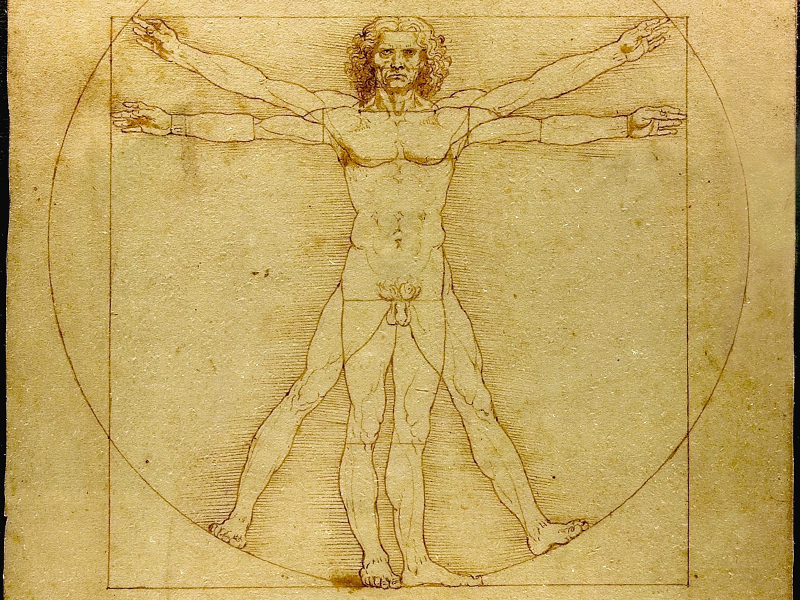

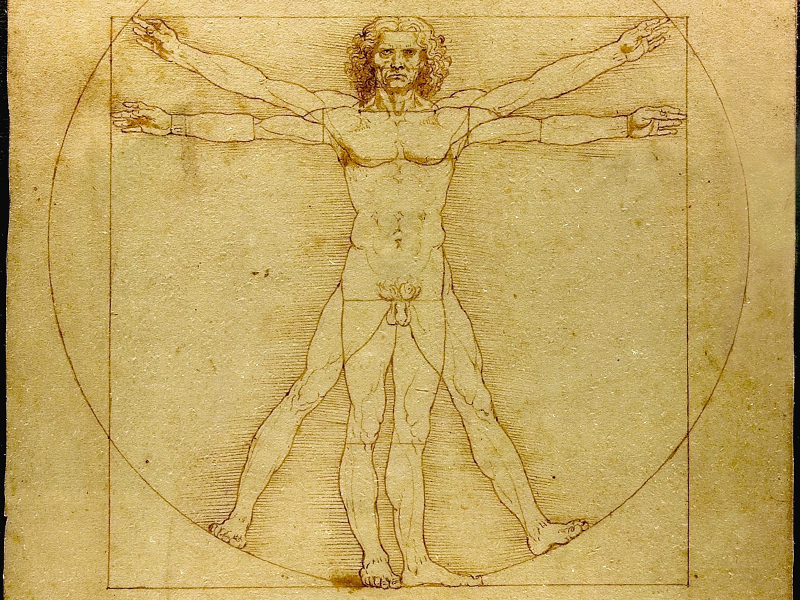

Ultimately, we need to recognize that one cannot live without the other. While STEM and business are great for sustaining a livelihood after college, studying the humanities helps us make sense of our lives and our world. People study English, art, history, music, philosophy and the like (even the sciences, in many ways) because it appeals to our innate curiosity, our desire to constantly question the claims of all authorities, whether political, religious or scientific.

Through the humanities, we think about what we are, where we came from, what we can be and should be. The STEM individuals of the world are responsible for the incredible advancements in science and technology that have made us a distinct generation of humans. But I cannot imagine a world where we never ask if those advancements are morally advantageous in the first place.