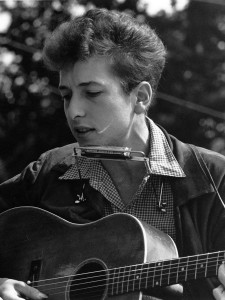

In 2012, the permanent secretary of the Nobel Committee, Horace Engdahl, made a controversial statement that “American literature is too isolated, too insular,” prompting fears that the Swedish Academy had ruled out American writers for the prize in the foreseeable future. With this statement, and the recent trajectory of Nobel prize winners being authors not very well known in the West, the likelihood of legendary singer-songwriter Bob Dylan winning the prize was faint.

And yet despite the odds, this year the Nobel Committee actually awarded Bob Dylan the coveted award, placing his name along with greats like T.S. Eliot, Ernest Hemingway and Toni Morrison. However, this decision has been incredibly controversial, with many claiming his work as a lyricist is not enough to merit serious consideration to Dylan as a writer, let alone a Nobel recipient. Many are arguing that because his lyrics are tied to his music, his work can’t be considered poetry. As such, he is undeserving of the Nobel Prize in Literature.

However, this view contends that the only way a lyricist could win the Nobel prize is through the power of poetry. This idea is gravely mistaken — nowhere did the Nobel Committee claim that Dylan is a “poet” in the traditional sense. His award was given for “having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition.” This clearly suggests that this award was not given to Dylan’s capacity as a poet, but his influence as a songwriter, which is clearly within the confines of what constitutes as literature.

Furthermore, outside of the schematics of his award, I posit that Dylan is a noteworthy candidate regardless of whether his idiom is poetry or song lyrics. From the dawn of literature, poetic expressions have had a tenuous relationship to human speech and song — from the Greek myth of Orpheus who invented poetry with his song, to Homeric epics which were specifically oral, the line between song lyrics and poetry have always been blurred, especially so in non-Western literary canons such as African and Indian literatures. Dylan’s lyrics have explored such a vast variety of themes and ideas, and he has experimented with lyric structure in countless ways to merit this inclusion.

In fact, the seminal “text” which shaped the Nobel Committee’s decision was Dylan’s 1966 album “Blonde on Blonde,” which is largely considered one of the most elegantly structured and written albums of all time. By turns, world-weary, heartbreaking and hopeful, “Blonde on Blonde” explores themes through intricate lyricism. This album would go on to inspire and reconceive traditional ideas of songwriting. By using concentrated and poetic details to carry narrative threads, Dylan revitalized the expressiveness of American folksongs. For example, the beguiling song, “Visions of Johanna” uses these details in an incredibly unconventional manner: “Inside the museums, infinity goes on trial / Voices echo this is what salvation must be like after a while.” I dare you to say those are not gorgeous song lyrics.

Furthermore, Bob Dylan belongs to a generation where literature and music commingled in many untraditional ways. Beat poets such as Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac — who were also friends of Bob Dylan — actually focused on bringing poetic idioms closer to human and regular speech. For the beat and counterculture generation, the idea that song lyrics did not constitute an important form of literature would have been absolutely absurd: This was the language of protest songs and political chants.

By opening up the Nobel prize to Bob Dylan, the territory that “serious” literature occupies has dramatically shifted for the better. It is imaginable that perhaps even Bruce Springsteen or Patti Smith may one day receive the prize with their multi-genre work.