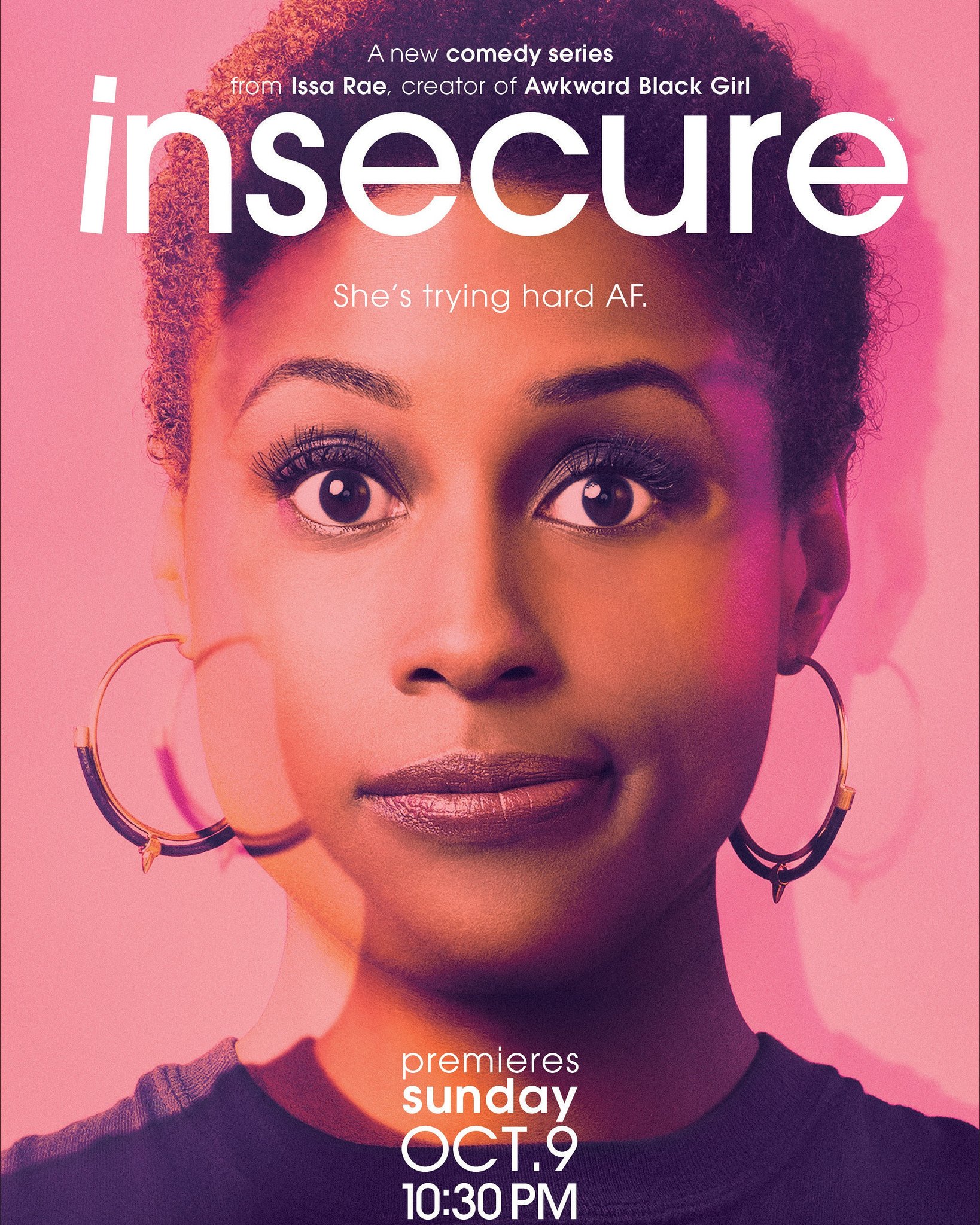

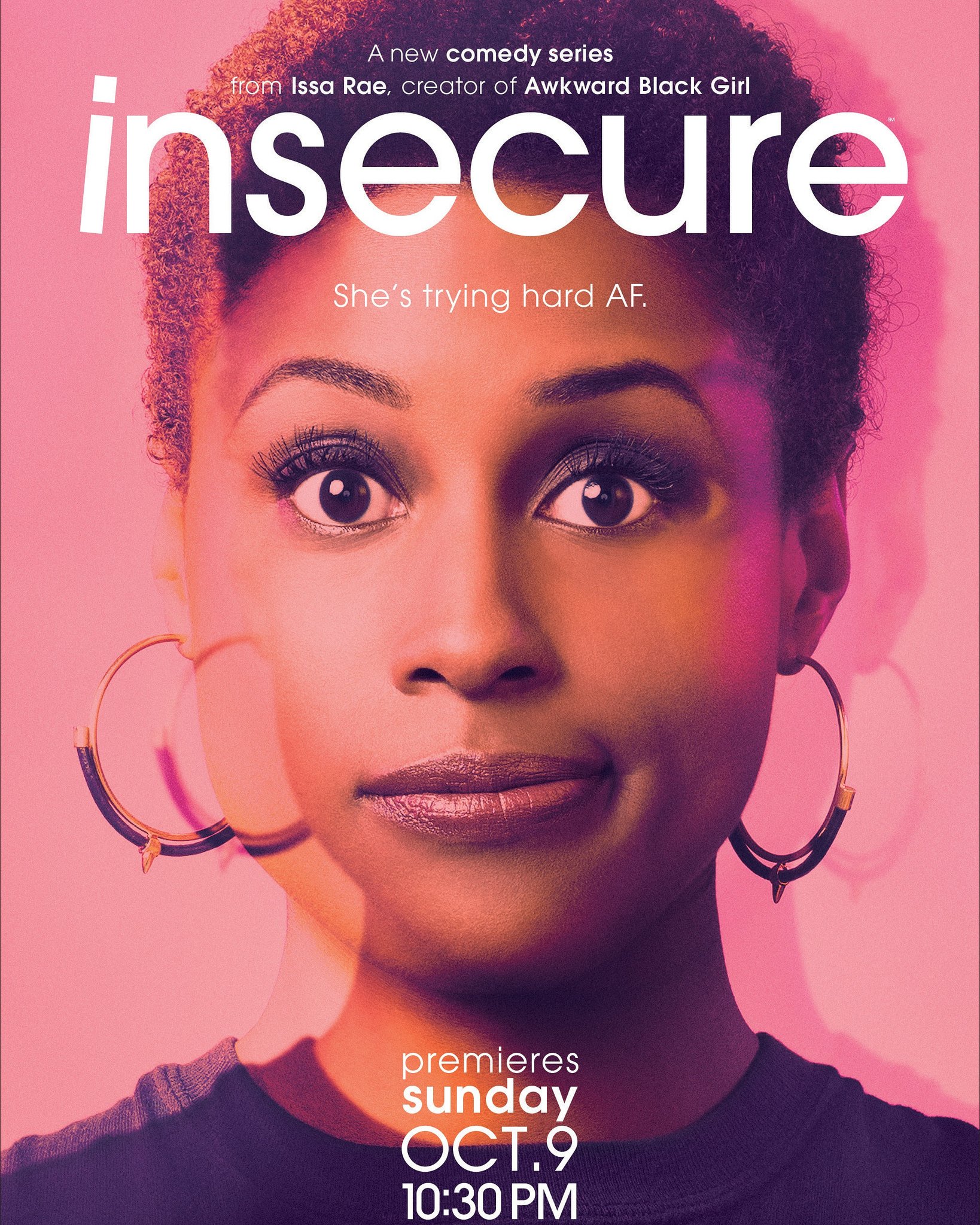

Tourist destinations cast an elysian Los Angeles on a laminated postcard. Their idyllic 8×5 sheen is an indulgence of city myths like the grandeur of the Hollywood sign or Venice Beach just above the 10 freeway. When Hollywood’s cameras visit the sparse neighborhoods of south Los Angeles they imperially blur their unique territorial idioms with gangster and cholo filters, as with 1988’s “Colors” or, more recently, 2012’s “End of Watch.” This superimposed filter streams an imagined south LA rather than a visceral one. Issa Rae’s HBO series “Insecure” fervently crowns itself in Inglewood, more interested in south LA’s ether than the idyllic myths above the 10. It’s an unwavering cinematic commitment to showcase south LA’s civic vibrancy, a parallel to the lives of its 20-something characters Issa Dee (Rae), Molly Carter (Yvonne Orji) and Lawrence Walker (Jay Ellis).

“Insecure” garments south LA with intricacy, seamlessly moving through the city’s history and changing identity; it serves as a congruence between recent versions of LA like “La La Land” or “Straight Outta Compton,” neither entrenched in its era nor conjuring a disconnected fantasy version of modern LA. The show wears LA’s history and future with comfort and palpability that enriches rather than mummifies its more historical locations like popular jazz and blues club Mavericks Flat in Leimert Park.

The show’s smaller vignettes, like Dee jumping out of bed to move her car because of street cleaning, shows “Insecure’”s familiarity with the city’s mundanity. Rae’s goal, as she tells the Los Angeles Times, is “to be like Woody Allen for LA … I love the culture and I feel like there are so many different pockets of riches that I want to depict for black and Latino culture that (are) not really acknowledged.” The show’s attention to detail, quirks and color reminiscent of Allen’s early work, makes “Insecure” a visual treat. Rae, alongside executive producer Melina Matsoukas and cinematographer Ava Berkofsky rectify institutional mistakes of inappropriately lighting darker skin actors and fine-tune south LA’s color scheme, often with wide shots characterizing the vibrancy of the city — a composition many Angelenos familiarize themselves with the city by the wide windows of their cars. It’s a metropolitan characterization of LA grounded in the colors, motion and music of south LA instead of its rich indulgences, like in Judd Apatow’s “Love.”

Rae’s comparison to Allen is an easy one for their shared civic devotion. A sharper equivalency would be Rae and Matsukas to Kahlil Joseph’s work for Kendrick Lamar’s “Good Kid Maad City.” Joseph and Lamar’s interweaving of Compton lore like the Compton Cowboys, using glitchy homemade family videos and magical realism — like homies hanging off the liquor store ceilings and lampposts — oscillate between reality, fantasy and abstraction. “Insecure” gravitating toward a dry realism rather than Joseph and Lamar’s art house cinema doesn’t bisect the shows magic quality of color, framing and music. Realism, too, can pocket a magic of the mundane like in the series’ opening scene. It’s nothing short of a love letter to south LA as Lamar’s “Alright” blasts through cruising shots of south LA staples: The massive doughnut of Randy’s Doughnuts, mandatory rows of palm trees and crispy dry green front lawns of ‘70s dingbat apartments like Dee’s The Dunes. Like Joseph and Lamar, Rae and Matsoukas poignantly shore an Inglewood brilliancy which grants the show to tread through delicate complicated issues like the gradual migration of Latinos to historical African-American neighborhoods like Inglewood and Watts.

One of season two’s plots places Dee and her liberal-leaning coworker Freida at Thomas Jefferson Middle School, where their afterschool program — which is supposed to cater to everybody — is only catering to its black students. The principal is responsible for discouraging the Latino students from attending the afterschool program and confronted by Rae and Freida the principal quips, “what is this all lives matter shit?” The principal’s resentment stems from a Latino student population edging out a once mainly black middle school.

The show could easily anchor down with overdetermined ambitions to calm the middle school race war all season, but instead it chooses to eloquently sketch out these relations that anchor the city. By the end of the season, Rae advocates for equal opportunities for all of its students, which neatly folds the plotline into a complicated problem that doesn’t resolve but acknowledges itself. “Insecure’s” attentiveness to characterizing the city allows it to tackle these complicated issues where other self-indulgent versions of LA would miserably fail at articulating the complexity of racial and ethnic relations. These relations aren’t exclusive to LA, but are unique to the city’s rapidly changing demographics and identity that “Insecure” is willing to thoughtfully discuss.

Change could just be another euphemism for gentrification in LA vernacular. Documenting or filming change queues the city in an ephemeral state, it’s difficult to grasp. Watching “Insecure” offers a mix of nostalgia and anxiety. The show’s instability stems from a looming gentrified future of south LA.

Attuned, I feel committed to remember the orange spectrum on Crenshaw or the layout of my local liquor store that any day could be turned into an art gallery or even equally as bad, a coffee shop. “Insecure” could also double as the name of the city of Los Angeles. Saccharine versions of LA mask the city’s uncertainty with a nasty pride as if whatever world it conjured won’t disappear. “Insecure” harkins to a Los Angeles unafraid to show south LA’s humming black and brown ecology thriving outside of Hollywood’s highway partite.