When I look back at my formative years from middle school leading into the beginning of high school, a tenderness fills my heart. I cringe a bit too, but mostly I smile — something I didn’t do too much of during that time, either for fear of shattering my image or because I hated my smile I can’t be sure. Surely I am not alone in these sentiments. As much as I refused to self-identify as such, I can retroactively say that I was an emo kid: Super skinny jeans, band tees, thick-rimmed glasses, straightened hair, ennui and all.

But where I can reflect fondly on these years now, a deeply wedged and excruciating embarrassment occupied my thoughts in the years that followed that phase. Nobody, save for the kids you saw on YouTube in 2007, proudly claimed to be emo, least of all pimple-faced 13-year-olds who borrowed their mothers’ straighteners at 6 in the morning and championed the platitudinous idea of individuality over societally enforced labels. I even started listening to T.I. and Lil Wayne in an attempt to prove that I wasn’t emo, something I do now, only now I do it because I actually like the music instead of trying to deflect ridicule.

The tides of popular culture wax and wane in mysterious ways, and recent years have seen emo music and its accompanying subculture evolve from punchline to legacy. The origins of this shift aren’t clean-cut, but early mainstream pop-punk and pseudo-emo bands like post-“Take This To Your Grave” Fall Out Boy, Panic! At the Disco and Paramore have played substantial roles in the evolution of the music genre.

Long before Gerard Way would birth a surge of emo tweens with their seminal “Three Cheers for Sweet Revenge” record, before kids would stumble upon Chiodos and Scary Kids Scaring Kids on YouTube and be introduced to screamo and post-hardcore, emo was aggressively antithetical to its contemporary pop-influenced iteration.

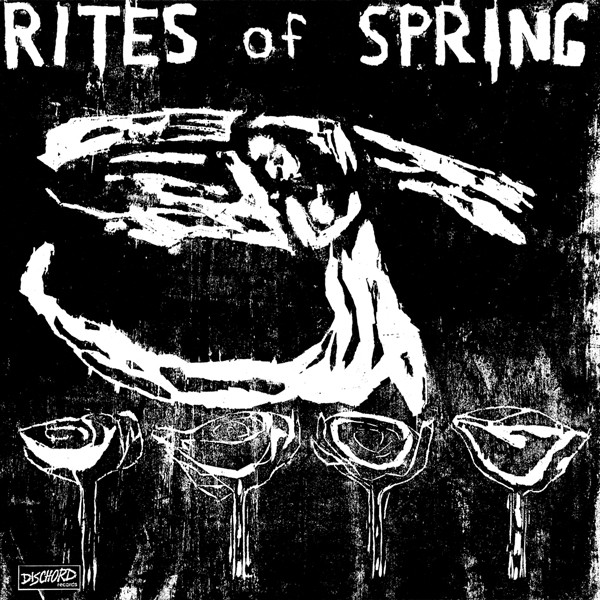

It’s been documented to the point of banality that Rites of Spring are the forefathers of emo music, but as Thomas Lloyd of the band Northvia points out, “what one person defines as ‘emo’ is not to the next, it all depends on the point of view.” Is emo a genre defined by its technical features, which itself varies from band to band? Compare the gleam of the guitars on American Football’s “Never Meant” to the blitz of Joyce Manor’s “Orange Julius;” contrast Britty Drake of Pity Sex’s hushed delivery on “Drawstring” versus Billy Talent’s Ben Kowalewicz’s screaming on “Line & Sinker.” Or more broadly, is emo an ethos characterized by emotional sincerity and dejection? All answers seemingly result in contradiction, though the latter answer continually feels more correct when artists associated with the term come under closer scrutiny.

To make a sweeping generalization about all types of music, it’s fair to state that expressing emotion and personal strife isn’t a novelty that emo alone embodies, but its grueling emphasis on sadness and isolation are what make it noteworthy.

From D.C. basements to suburban bedrooms, emo’s gradual ascendence out of obscurity inevitably came with the cost of sterility and integration with other genres. Fate meted out the former consequence in the form of some radio-friendly hits and, eventually, shit-tier derivatives that would gain cult followings through the internet (nature gives and she takes). More excitingly, musicians outside of rock subgenres would develop their own sounds inspired by emo’s emotionally bare ethos.

The most popular genre of music per Nielsen’s Music Report is (surprise!) hip-hop. To synthesize what can rightfully be declared the whitest music genre ever with the quintessence of contemporary black art is not without its mishaps (see: Brokencyde and the entirety of the crunkcore movement). In spite of how corny it might have read on paper in years prior, their commonality of lyrical vulnerability bonds the multi-faceted genres closer.

“My shit is like emo music for gangbangers,” said LA rapper 03 Greedo in an in interview with LA Weekly. Greedo’s music is soaked in emotion much in the same way gangsta rap by the likes of Bone Thugs and Pac was in the ‘90s, mourning the loss of close friends and documenting the crippling realities of street life. His relation to what we understand as emo is thin, but if it’s to be believed that the essence of the music is laid bare for heartache to occupy it, the self-proclamation rings true.

Emo’s big break among the hip-hop community came in 2017, with popular Soundcloud rappers like Ka5sh, Trippie Redd, XXXTentacion, the late Lil Peep (along with the entirety of the Goth Boi Clique) and, most prominently, Lil Uzi Vert. This is where the intermingling of genres gets exciting. Where Kanye paved the way for artists like Kid Cudi and Drake with his raw and deeply personal “808’s & Heartbreak,” young artists raised on Marilyn Manson and Taking Back Sunday would firmly define emo for a new generation.

Does it bring pause to reflect that one of the top songs of last year was a post-breakup cut of maudlin rumination? Uzi’s “XO Tour Llif3” is a lovelorn confessional not too dissimilar to prototypical emo ballads like Hawthorne Heights’ “Ohio Is For Lovers,” where Xanax-popping trades places with wrist-cutting and nail-painting. Self-harm was never the lure of emo per se, but it’s willingness to be open about such difficult subjects is precisely why kids can find solace in these artists’ music. It’s why Lil Peep was the monolithic figurehead of the movement before his tragic death in November, crying for help when he sang in his characteristic Tom DeLonge-resembling voice, “I used to want to kill myself/ Came up still want to kill myself/ My life is going nowhere/ I want everyone to know that I don’t care.” Along with fellow GBC members such as Lil Tracy and Cold Hart, their sampling of The Microphones, Bright Eyes and Modest Mouse paired with rabid cult followings foreshadow the steadily evolving genre that acknowledges its roots.

18-year-old Ohio native Trippie Redd developed a dedicated fanbase online with the release of his two-part “A Love Letter To You” mixtapes, fortified after his collaboration with Florida rapper XXXTentacion on “Fuck Love.” Unfortunately, it’s with rappers like X that emo’s less-than-desirable relationship with women returns to mind. His highly publicized domestic abuse case still looms over his name which, while miles away from the latent misogyny in most emo classics, is nonetheless a case of old habits dying hard. As Junkee’s Allison Gallagher writes, “As a 25-year old, listening to young men objectify the women in their lives and vilify those who chose to leave is a bitter pill to swallow.” Paired with hip-hop’s shaky relationship with women (calling women “bitches” in rap is so commonplace it’s easy to mistake it for the moral convention and not the anomaly it is in casual conversation), emo rap still has a long way to go before it dusts itself off from its parent genre’s blemishes.