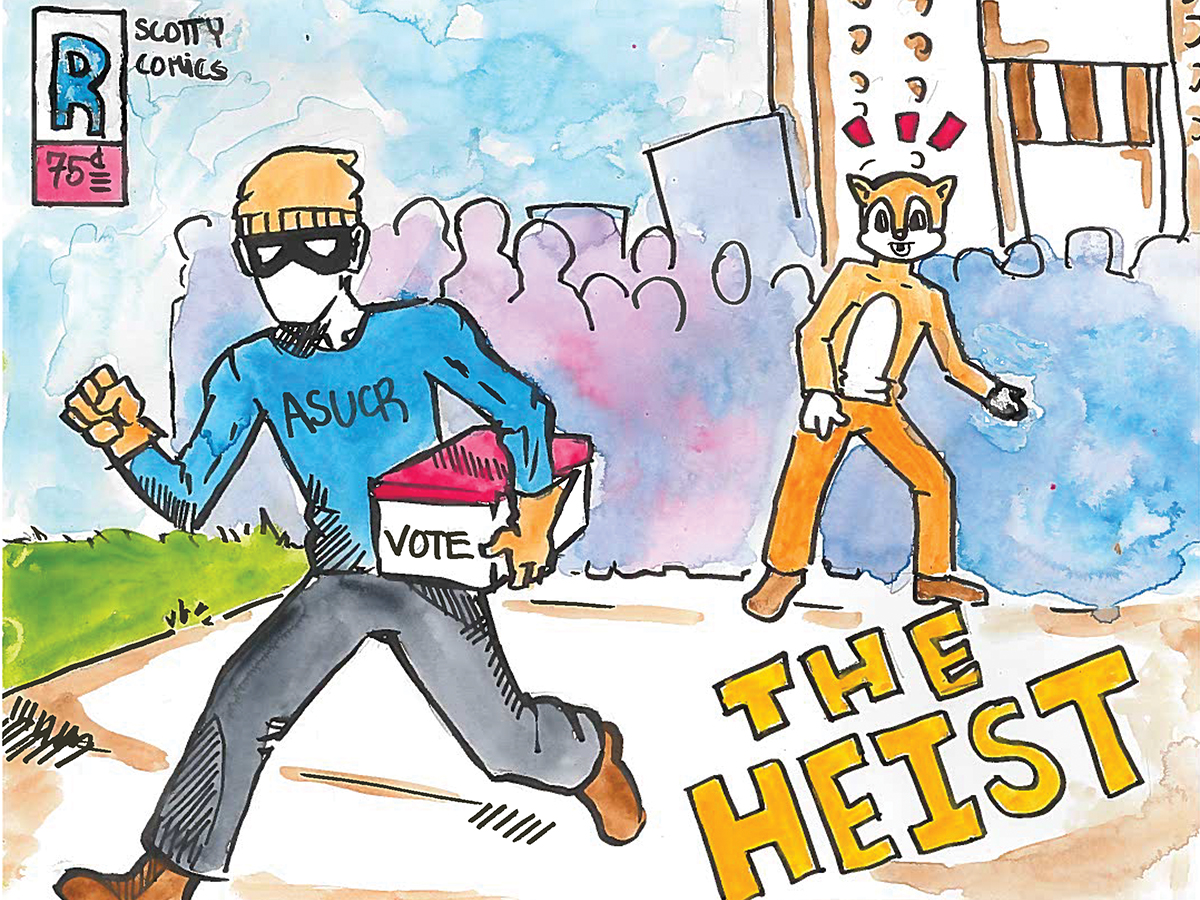

Elections Director Taylor Brown announced the results of the 2018-2019 ASUCR elections last Monday, and while there was quite a bit of applause and cheers for the new executive cabinet members and senators, there was far less enthusiasm from the proponents of the three referenda on this year’s ballot. Because only 2818 students voted (about 14.39 percent of the undergraduate student body), the referenda failed to meet the minimum threshold of votes to be considered valid, which is 20 percent of the student body, per Section 84.12 of the UC Office of the President’s policies. Thus, all three referenda failed — despite each receiving an overwhelming majority of “yes” votes. There was no such threshold for the executive cabinet or senator positions.

Notably, a write-in presidential candidate under the pseudonym of “Furry Boi” (AKA, second year environmental science student Timothy Hughes) earned a sizeable 113 votes. Hughes didn’t earn nearly as much success as UC Berkeley’s own iteration of Furry Boi, a sophomore by the name of Stephen Boyle, who won a senate seat in Berkeley’s student elections back in April while running as a joke. Nevertheless, both this year’s incredibly low voter turnout and the fact that Hughes got such a sizeable portion of the votes, despite being an actual joke candidate like Boyle, underscore the issues with not only this year’s ASUCR elections, but the state of student engagement with ASUCR in general.

It is necessary to have some kind of minimum threshold of votes for referenda in order to make sure that said referenda actually have some form of popular support before their supporters can change student fees. However, the fact that there were only paper ballots and no online voting this year (as an effort to prevent the prohibited tactic of laptopping) doubtlessly contributed to this historically low turnout, as this gave students no option to vote without having to wait in line at polling sites in the midday heat. This is to say nothing of the fact that many classes begin their midterms around week four, the same week of the elections, thus forcing students to choose between getting in last-minute studying for the sake of their grade or waiting around in line to vote in-person, as opposed to simply being able to log in, vote and get back to their studies.

Thus, the issue is not with the threshold in itself, but the fact that the groups supporting each referendum weren’t given the option of online voting, the tool that would have helped them reach 20 percent turnout. Laptopping shouldn’t be allowed to return, and having any form of online voting invariably opens up that possibility to candidates who somehow can’t manage to obey the rules and leave busy students in peace. Still, it is incredibly unfortunate and disappointing that the referenda weren’t able to pass (despite landslide support from the students who actually voted) because of the lack of convenient online voting. It’s also strange that this threshold wasn’t applied to the candidates themselves, who will now go on to be paid — some, nearly $10,000 — for their new positions in ASUCR. Of course, you can’t simply leave the student body without representation from a student-led government, so you couldn’t deny all the senate and executive cabinet winners their victories based on not meeting the voting threshold. However, one also has to wonder how much more ASUCR would do to promote voting and interact with the student body if the candidates did indeed have to meet a threshold to be considered legitimate.

Whether there is a threshold or not, it’s clearly unbalanced to hold senate and executive cabinet candidates to one standard and referenda to another. Though we aren’t calling for results to be overturned at all — rules are rules, even if they are questionable — it’s very dubious whether the victories of the new senate and executive cabinet members are, in any way, more representative of what the students wanted than the “failure” of the referenda, all of which earned more “yes” votes than most of the candidates who ran unopposed.

On the subject of opposition, the fact that “Furry Boi” squirreled away 113 votes as a write-in candidate using largely grassroots campaigning is a scathing indictment of ASUCR’s value in the eyes of the students. Though each voter who wrote in Furry Boi had their own reasons for writing him in, these votes can largely be considered a form of protest, either against both of the real candidates or against ASUCR itself. His voters don’t seem apathetic about the elections as a whole; after all, if they were merely apathetic, it would have been more convenient to just not vote. Rather, even if it was just because the idea of a Furry Boi presidency was amusing, those who voted for Furry Boi did so because neither of the other options were compelling enough to earn their vote, or because they did not believe that the winner of the presidency would make a difference in what ASUCR would do for the campus. Such protest votes are a completely valid and important means for students to express their discontentment with what ASUCR has and hasn’t done for them.

The new ASUCR regime must learn from this year’s abysmally low voter turnout and the copious number of protest votes and resolve to fix the problems that plagued this election. The fact is that this year’s referenda will not be implemented while the new regime takes power, even with only 14.39 percent of the student body’s vote to validate that power. The onus is now on the winners of this election to reassess what has led to this and lay out directly to the students what they plan to do. If ASUCR expects to be able to say that they represent students, it’s incumbent on them to engage and be transparent and accountable with all students on not just their victories, but also their faults. Not only is this their duty as elected student representatives, it’s their responsibility as the victors of this past election to ensure that the next one has much more student engagement, with an outcome that is actually representative of what the voters want.